Roddy Parker brings Andrea Arnold and her sound practice, which exists throughout her body of work, onto display. Part of the second wave of British Socialist Realist filmmakers, Andrea uses diegetic sounds to convey meaning, many times multilayered and malleable to the situation the sound is used for.

About halfway into Andrea Arnold’s Academy Award-winning 2003 short film Wasp, her protagonist Zoë, a struggling mother of three, pushes a glass of coke into the hands of her reluctant eldest daughter. They are standing outside a pub in Dartford, Kent and Zoë has hastily scampered out armed with bar snacks for her three unattended children. They sit outside while their mum attempts to have a romantic evening with a heartthrob from the past. “Just take what you’re given” she says, pressing the glass into the small hands of her daughter Kelly. Moments after, the late 90’s pop group, Step’s 1997 hit “5,6,7,8” begins to emanate from the pub’s open doors, bleeding out into the parking lot. Zoë lapses for a moment from her frazzled pleas and hushed swearing into a faintly desperate but animated dance, cajoling the idle children into joining her in a goofy rendition of the track’s infamous routine. For a brief moment, the four of them sync up into a surprisingly coherent display of hip waggling and invisible lasso swinging to the distant music, before Zoë heads back inside the pub, leaving the three children alone once more.

This moment in the film exemplifies its director Arnold’s delicate and intentional usage of sound within her work. Or rather - her trademark absence of nondiegetic music, and a focus on the organic and second hand. Whilst hesitant to claim any such title, Arnold is very much seen to have picked up the torch left simmering by Ken Loach, representing a second generation of British Social Realist directors, continuing to depict unheard tales of deprivation and neglect into the noughties. Alongside directors such as This Is England’s Shane Meadows and Dirty Pretty Things’s Stephen Frears, Arnold is a filmmaker known for shining a spotlight on stories that take place on the margins of British society. She has a unique and singular talent at unearthing the quiet brutality embedded within urban mundanity. At excavating pathosian narratives from pebble-dashed landscapes of destitution and abandonment. In Wasp, as in all of her early works, no score is used, there’s no compositional accompaniment to its striking visuals. The dominant sound within the film comes from recordist Neil Robert Herd’s microphone: the wheels of a pushchair (stroller) scraping gravel, the fogged humming of a motorway beneath an overpass, background chatter in a smokey pub. Until its closing shot (set to the tune of a not-so-subtly foreshadowed dance pop hit) the only sound emitted during the film is diegetic. It bleeds out of a pub’s doors or the window of a passing car. Elsewhere, originating from a children’s toy Zoë’s daughter plays within the kitchen of their flat. In a film depicting the tenuous balancing act of human wants and human needs, Arnold’s usage (or lack thereof) of nondiegetic sound, advances its message sonically. Its protagonist Zoë navigates this web - yearning for human connection whilst weighed down by the job of supporting her children, unemployment, and being denied basic human indulgence by economic constraints.

Wasp Theatrical Poster (Source)

Ken Loach’s This Is England (Source)

Andrea Arnold (Source)

Arnold's resistance to formal soundtracks feels like an intentional defiance of cinematic convention. As Zoë fiercely makes out with a brilliantly case Danny Dyer in the front seat of his scraped up hatchback, her children glumly wait in the now moonlit pub’s car park, no soaring strings float upwards. Only the smacking of lips and snarling wisps of smushed nasal breathing, the clunk of a seat being hastily reclined, soundtrack this tantalized moment of passion. These flashes of intimacy are short-lived and rough around the edges, unglamorous and human. This teased reward for Zoë, her hard-fought prize that she has sacrificed reputation and peace of mind for, is immediately cut short by the titular wasp’s attack and ensuing wails of her children from the car park.

This is just another instance of how a calculated restriction of musical sound helps to reinforce Arnold’s trademark theme of deprivation. Through its intended absence, music becomes a valued commodity, and the moments in which it is gloriously permitted are intentional. Happiness in these landscapes of hardship is a similarly rare commodity, and the two are paired by Arnold - never oblivious to the joys and beauty present in all walks of life; the viewer/listener is denied access sonically, reflecting the characters’ material and emotional desires. When these fleeting moments of happiness (in keeping with her socio-economic awareness, typically synonymous with stability - be it financial or emotional) emerge within the neglected environments that Arnold’s characters maneuver, music is permitted. Music and happiness seem to align, an intentional rush is ushered in, one which the viewer and characters experience in tandem through this tactile deployment of recorded, nondiegetic music.

(Source)

An example of this occurs in Arnold’s 2009 feature-length Fish Tank, when teenage protagonist Mia’s search for attention and nurturing comes closer to realization. Her mum’s new boyfriend Conor (a wolfish Michael Fassbender still wearing his sheep’s clothing) takes the family on a spontaneous drive, the day trip a respite from Mia’s relentlessly horny and sometimes overtly neglectful mother’s inattentiveness. Traveling somewhere just for the fun of it, included for once, her presence requested rather than ordered, the hint of a smile creeps into Mia’s usually hostile features as Fassbender launches into a wonderfully dad-core rendition of Bobby Womack’s “California Dreamin’”. Here, music is being awarded, shared - “It’s time to educate you girls”- by a newly introduced father figure who is making time for the girls. As pylons pass outside the car’s windows, peppering an alien green backdrop of foliage, Conor taps away at the steering wheel and Mia begins to rock slightly, her body language a reluctant giveaway as musical pleasure is paralleled with emotional nurture, its sonic presence emphasizing the significance of the moment.

Ever the defyer of binaries however, the rare musical moments in Arnold’s early films never reinforce a single emotion. Rather the significance of whatever emotion is taking place within the protagonist at that point in their narrative arc. In many of her films, what appears to be a positive signifier earlier in the film - music paired with moments of hope, growth, connection - is often later on used in the same way to reveal something darker. It is not always a simple equation: music = happy. A more accurate formula would be music = rarity, significance. Music becomes a primal, autonomous force, taking on a life of its own, a tool to accentuate nuance rather than provide any definitive answers. An example occurs later on when the same Womack track plays under vastly different circumstances as Mia, confused and unfamiliar with any sort of kindness, dances for Conor in the dark living room of their council flat - intended no doubt as a statement of gratitude, of respect: You showed me this, now I have chosen to use it for something I care about (she uses the track to show him her latest dance routine). Moments later, a predatory Conor begins to push himself onto the confused teenager, revealing his true nature, the two of them entering into a physical relationship. Her juvenile confusion is heartbreakingly apparent, his cruel manipulation and exposure as a predator destroying any hope that had arisen to the tune of the same song earlier in the film.

Fish Tank (Source)

Elsewhere this allowance of music within the world of the film mirrors the structuring of these scenes. Time and time again in both Fish Tank and Wasp, music’s rare second-hand presence is utilized to emphasize the significance of key plot points and character development: Fassbender’s affection and the effect of this nurture upon the hostile Mia, the corruption of this affection and painful betrayal in his opportunist advances. The first time we see her really let loose and display any kind of visible passion, Mia dances in an abandoned flat as Eric B and Rakim’s “Juice (Know The Ledge)” plays out of a tattered CD player. The track is blown out and tinny, played as it is within the physical space. All of the musical selection is refreshingly authentic, in the same way that “California Dreamin’”has no real pertinent symbolism to it, “ Juice” too isn’t there to make some lyrical or melodic advancement of the moment it is serving to highlight. They weren’t brainstormed by a music supervisor: hmm what song would truly reflect the emotional impact of Bobby and Mia’s connection in that scene? Both tracks are just what song would probably play in those moments. In the same way “5,6,7,8” was an early 2000s unofficial pub classic in the UK - it doesn’t have any special meaning when paired with the plight of Arnold’s characters. Musical presence alone is the accentuator, the quiet instruction to an audience to pay attention, to realize that something special is occurring, be it good or bad. In 2006’s Red Road, the Scuba Z track “The Vanishing American Family” plays in the late hours of a party in a Glasgow council flat, soundtracking a key plot point as protagonist Jackie draws close to her husband’s murderer. The night is winding down and boozing couples come together to slow dance in the living room. The song is tender - but like the rest of the film’s limited soundtrack (Oasis, Honeyroot, DJ Casper), it’s just what would be playing in those moments. Again, Arnold’s characters get what they’re given musically, the selection doesn’t stray from the film’s realism, its authenticity.

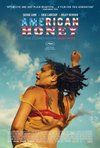

A clear shift in Arnold’s approach to music can be seen when she has strayed from these subjects in recent years. Later works set in America for example, residing more in the blockbuster vein, don’t harness the techniques of her earlier works quite as much, their legacy is present nonetheless. 2016’s American Honey, for example, retains hints of these earlier sonic deployments by Arnold - the midwestern road trip tale containing plenty of car stereo singalongs - but sits farther afield from the director’s baseline setting and cultural roots. These later, high-budget mass viewership works can’t help but bend the knee a little bit to soundtracking convention. The Hollywood-ization effect is somewhat inescapable, with a few obligatory sunroof-popped montages overlaid with nondiegetic music. In spite of this, we get the impression that Arnold has fought to maintain her sonic agenda even when directing the big leagues: she does a remarkable job of transposing her previously realist, anglocentric soundtracking into an American format: Oasis in a council flat becomes Rihanna in a Walmart, Wiley’s “Baby Girl” gives way to E40’s “Choices”in a midwestern parking lot. The geo-specificity of the era and music has adapted, but with long stretches of musical absence and a continuation of its presence within scenes rather than laid upon them, Arnold has resolutely stuck to her guns across her career. I wonder if perhaps this played a role in her mysterious booting off of the soundtrack heavy Big Little Lies third season?

American Honey (Source)

Regardless, Arnold has pioneered something special across her lengthy body of work, a distinct sonic methodology. Finding a way to reinforce a specific visual identity through its sonic accompaniment. A delicate balancing act which strives to construct a purposeful listening experience within a primarily visual art form. A consistent and renegade attitude to symbolism within soundtracking and the defiance of cinematic convention is a rare thing to land successfully. Whether this tactic translates seamlessly into the mainstream doesn’t really matter - probably to Arnold herself. She’s doing her thing. Her audience experiences through the ears of her characters, a longing for beauty. We understand the intended symbolism in music’s presentation as an ambiguous, commodified element. Arnold is working to underscore questions of accessibility and privilege by these sound choices: she takes a supposedly universal pleasure, and makes it scarce. Uses it to reflect the material struggle of her characters, to convey a commentary on deprivation through sonic means. From the early noughties through to the current day, her marginalized protagonists - whether sat outside the boozer in Dartford or under the halogen lighting of a midwestern mega-mart - must sonically “get what [they’re] given” and be content with it. Like most else in their lives.

Wasp (Source)