Music is more than melody, harmony and rhythm. Adrian DiMatteo looks at music as a tool to communicate: before language, as a loon call in war, as a way to indicate seasons and more.

The origins of human music-making are shrouded in mystery. Our musical roots are prehistoric; archaeologists uncover bone flutes dating back more than 40,000 years. Ancient musical traditions are found on every inhabited continent, and they share many striking similarities (such as prevalent use of the pentatonic scale). Nevertheless, the question, “What is music, and why did humanity develop it?” remains a matter of debate amongst musicians, scientists and philosophers. This is partly due to the fact that music has many functions — to entertain, commemorate loved ones, consecrate ceremonies, aid in memorization, and even call soldiers to war. In South Africa, drums were used “to send signals to neighboring tribes.” Music’s ability to convey human thought and emotion ranges from the explicit to the ineffable. Like bird mating calls or territorial gorilla hoots, human beings associate sounds with meaning to express feelings, warnings, and needs. Sound is one of the basic sensory resources humans have to make meaning and beauty out of reality. Therefore, music as a form of communication overlaps intimately with language.

At its heart, music communicates. Technologies such as drums produce deep sounds that can travel greater distances than the human voice, since longer wavelengths are less easily obstructed or absorbed by objects in the environment. For similar reasons, whistle-languages such as Silbo Gomero exist in various parts of the world. “La Gomera’s whistled language was invented because of the Island's geography...We didn’t have to walk up and down the mountains to talk to each other anymore.” Diverse cultures have developed complex instruments and uses for sound, both pragmatic and artistic. However, despite the universal principles that underpin music (such as rhythm, volume, and pitch), there is no objective meaning that we can ascribe to vocal formants (the building-blocks of language) unto themselves. Jean-Jacques Nattiez writes: “The border between music and noise is always culturally defined."

Image by Adrian DiMatteo

Jean-Michel Basquiat once said, “Art is how we decorate space. Music is how we decorate time.” Silence is the blank canvas on which sound is painted, and the silence within sound allows us to perceive changes in frequency over time. French composer Edgard Varèse defined music as “organized sound,” but this definition leaves much to be desired. A dial tone is organized sound, but is it music? Some say bird calls are musical, while others believe this to be a subjective human interpretation.

In The Music Instinct, Philip Ball writes that, “bird and whale songs...aren't mere screams or whoops, but consist of phrases with distinct pitch and rhythm patterns, which are permuted to produce complex sound signals sometimes many minutes or even hours long.” Neuroscientist, cognitive psychologist and author Daniel J. Levitin suggests, “...music may be the activity that prepared our pre-human ancestors for speech communication and for the very cognitive, representational flexibility necessary to become humans.” Although we can only speculate on early-human vocal behavior, nature has been a primary inspiration for human creativity.

Like language, music has aural and written traditions. The earliest known piece of written music, “Hurrian Hymn No. 6,” was composed in cuneiform and dates back to the first century AD. Since then, numerous systems of musical notation have emerged around the world. In the 8th century AD, Charlemagne led a campaign to codify musical notation throughout the Carolingian Empire. This served to unify diverse cultural groups, preserve music of the past, and enable the church to disseminate consistent transcriptions of liturgical hymns. Meanwhile, treatises on music theory and notation were already in print, such as, “Arithmetica, Geometria et Musica” by Boethius and, “Ars Grammatica” by Donatus. These titles — relating music to arithmetic, geometry and grammar — shed light on the intimate connection between music, language and mathematics.

“Hurrian Hymn No. 6”

Pérotin, "Alleluia nativitas", in the third rhythmic mode.

“The Coltrane Circle” by John Coltrane, titan of jazz saxophone.

Vibrations are oscillations of energy through time and space. Therefore, music inherently involves physics and mathematics. Consider the following formula as a definition of melody:

Melody = Notes over Time

M = N/T

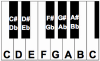

Throughout the world, 12 fundamental musical notes are commonly used. Each note vibrates at a specific frequency, such as “A” which is tuned to 440 Hz (or oscillations per second), according to the International Organization for Standardization. Humans can learn to identify musical notes by name just as they can identify letters, colors or shapes. Musicians who are native speakers of tonal languages (such as Mandarin Chinese) are more likely to have perfect pitch (the ability to identify a musical note upon hearing it) than speakers of non-tonal languages. These 12 notes are the alphabet of music. Various cultures have their own terminology to describe them, but descendants of the European classical tradition know them as:

Music notes on a piano.

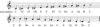

Music notes on a traditional musical “staff.”

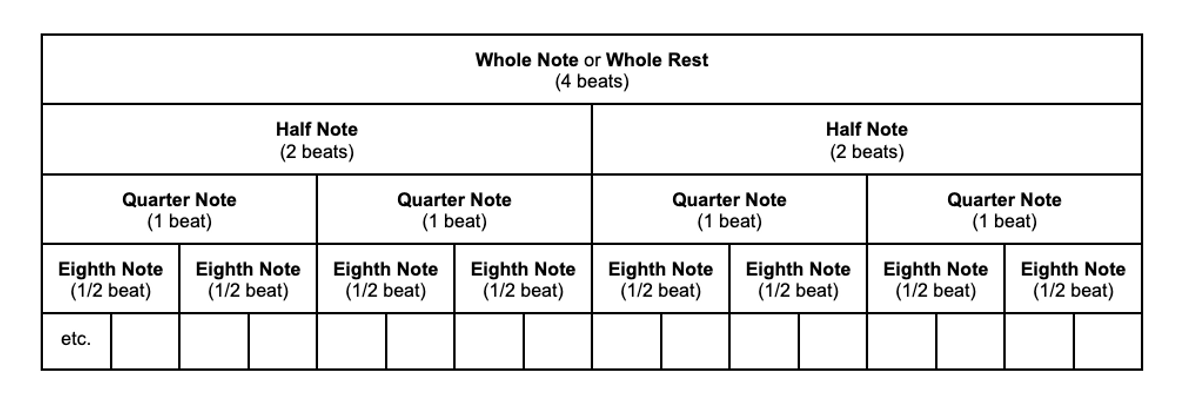

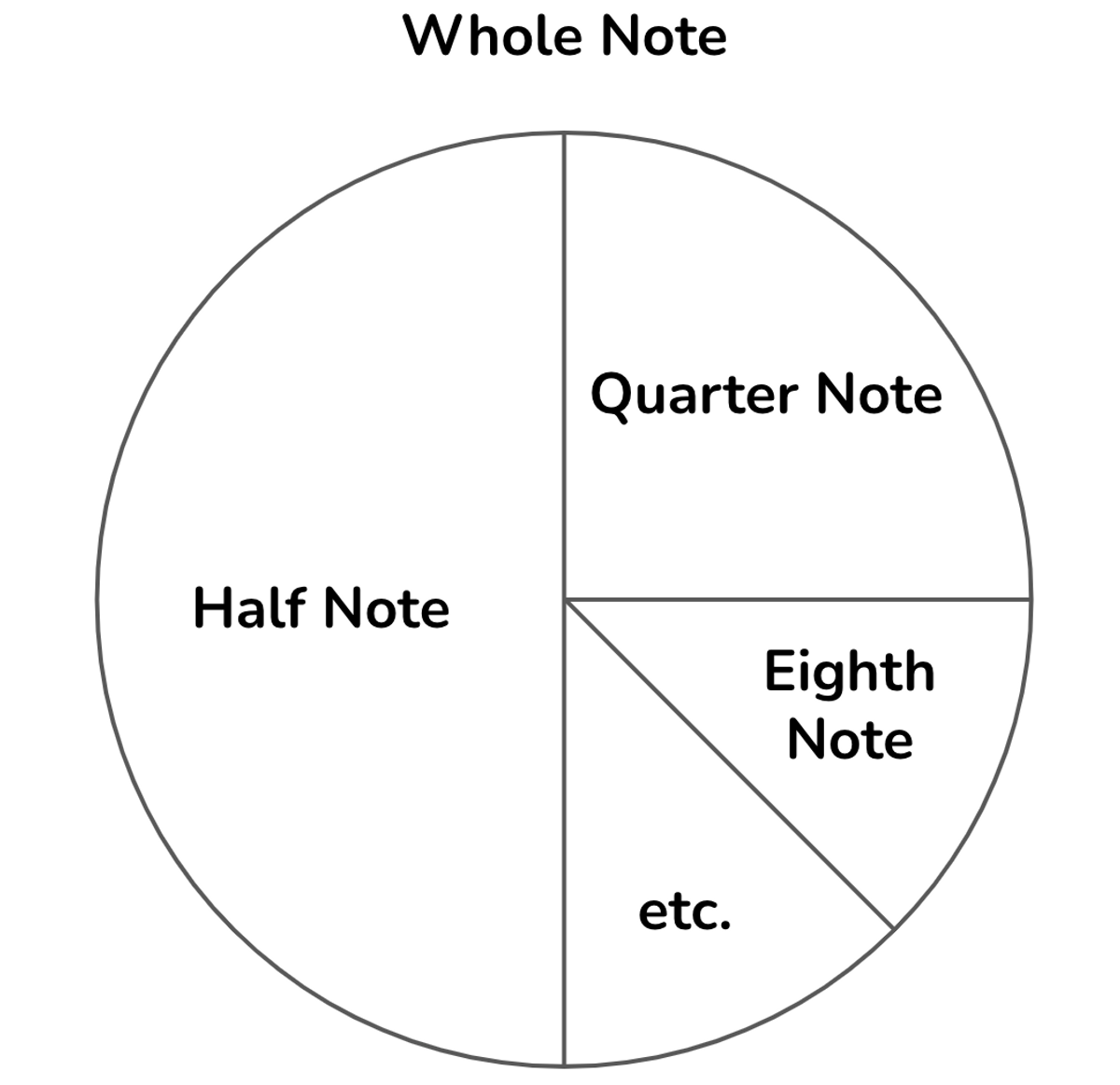

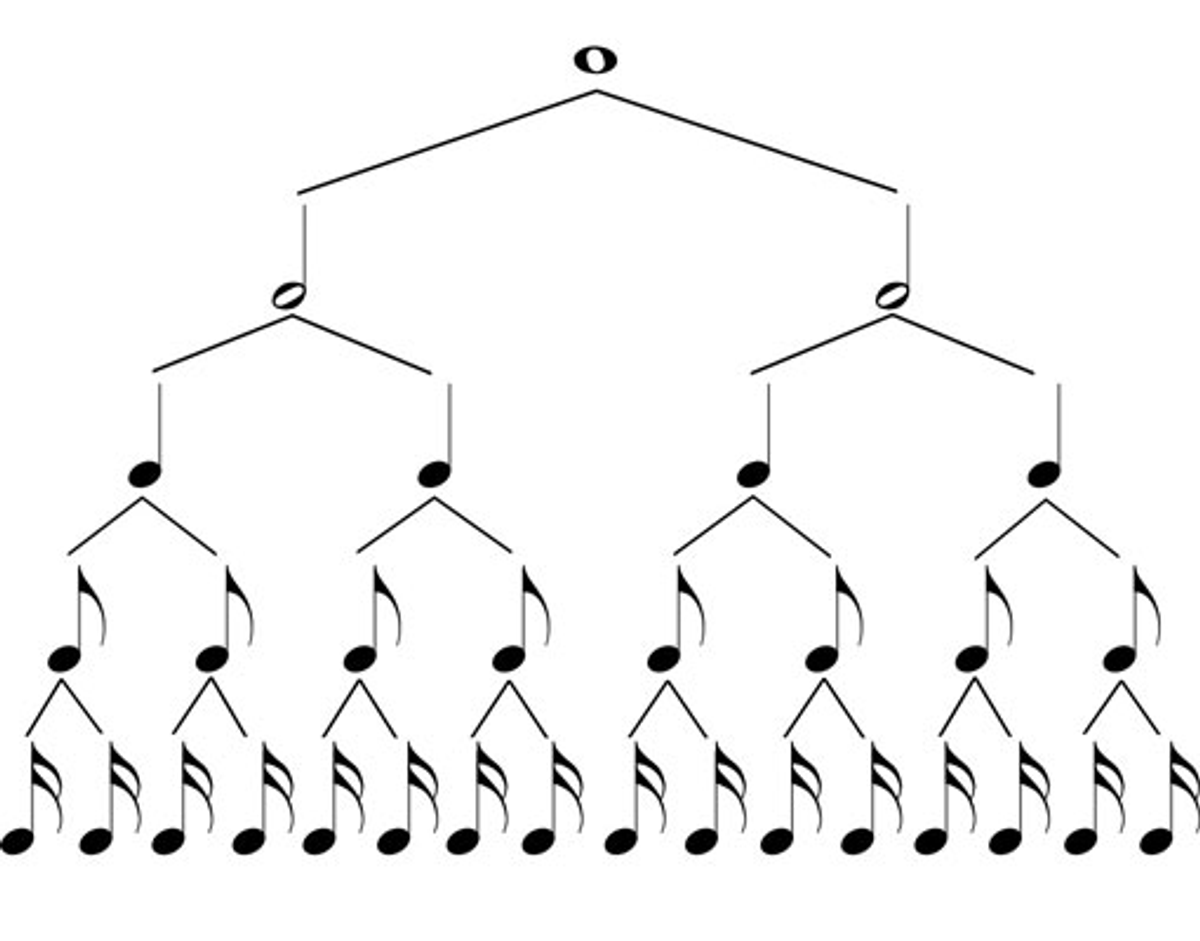

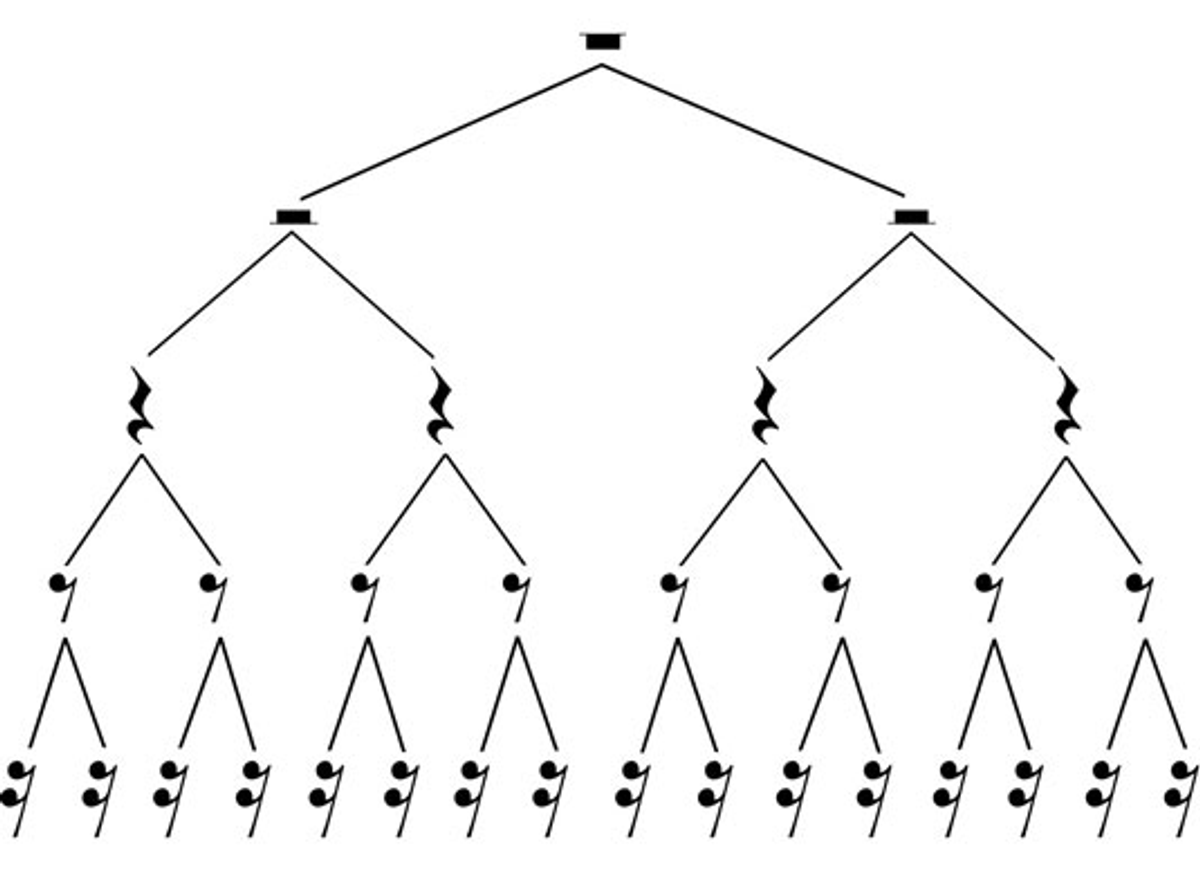

When notes are combined, more complex structures are created. In the same way letters are combined to make words and sentences, musical notes are combined to construct melodic phrases. These phrases are shaped by rhythms and rests. Rests function like punctuation marks, indicating where to pause or leave silence.

Image by Adrian DiMatteo

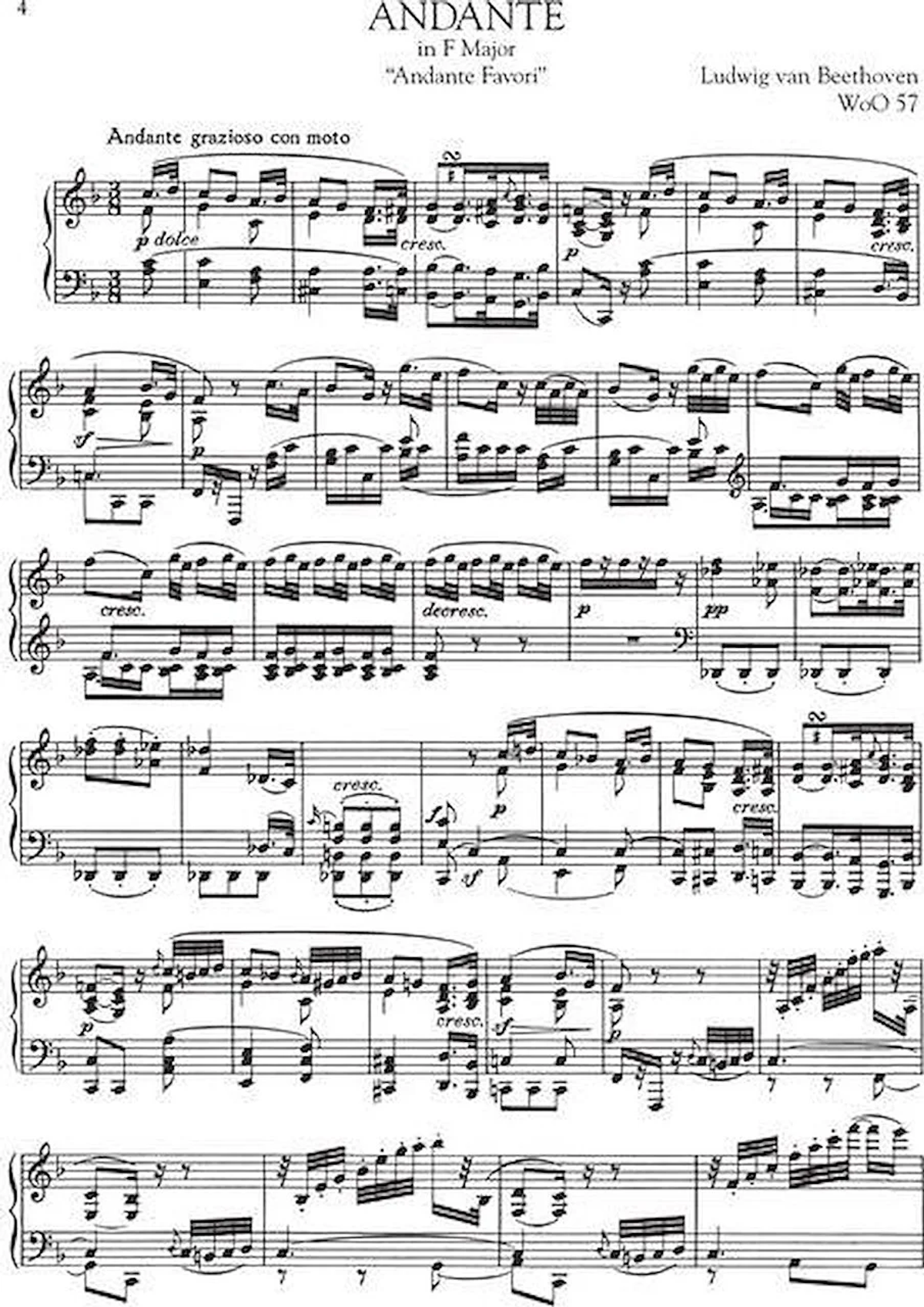

As a written language, music notation allows for an incredible level of specificity. There are codified rules for indicating notes, volume, speed, articulation, tone and duration. Musical notation even allows for multiple melodic lines to be played simultaneously. Can you read ten sentences at once? That’s what a piano player does when they recite music for ten fingers. Can 50 people talk to each other simultaneously? That’s what an orchestra does when performing a symphony.

Just as linguistic families adhere to grammatical and syntactical rules, various musical styles follow common practices regarding rhythmic and melodic phrasing, harmonization (how notes fit together) and compositional logic. 12 Bar Blues, AABA song form, toccata and fugue are a few examples of canonized musical structures. Similarly, a variety of poetic forms exist which require a writer to follow compositional rules to produce a sonnet, villanelle, sestina, haiku, and so on.

For the ancient Greeks, poetry and music were closely related. In fact, the term “meter” meaning “measure” is used in both art forms. Various meters such as “iambic trimeter” or “dactylic hexameter” were used to compose epics like the Iliad and Odyssey. Poetic meters make use of long and short (stressed and unstressed) syllables in strict rhythmic groupings. Similarly, musical compositions follow various rhythmic cycles to create patterns of stressed and unstressed beats.

Through music, composers imitate nature, express abstract philosophy, depict linguistic images, and even make explicit statements. Handel’s “Messiah” uses “text-painting” to evoke valleys and mountains with low and high notes. Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” follows the exact harmonic outline of the song’s lyrics, “It goes like this: the 4th, the 5th [as in the 4th and 5th notes of the scale], the minor fall, and the Major lift.” Atonal composers Anton Webern and Arnold Schoenberg broke with traditional rules of harmony to compose music that reflected the chaos and angst of two World Wars. Sergei Prokofiev used “leitmotifs,” or recurring melodic themes, to cue characters in Peter and the Wolf.

Text-painting in Hande’s “Messiah”

Music-making involves significant brain activity. Brain centers associated with emotional processing, language, motor skills and memory are involved in composition, practice, performance, active and passive listening. Our capacity to organize numbers, detect patterns and make meaning out of information allows us to form systems of logic and interpretation. Individual and cultural upbringing influence how a person understands sonic signals. Cognitive disorders can result in partial or total failure of a person’s ability to communicate or understand music and language. In reverse, music can stimulate neural pathways in patients with conditions such as dyslexia, alzheimers and age-related dementia.

In terms of evolution, some very ancient parts of the mammalian brain (including the auditory cortex) are used to produce and process sound. Because sound is a primary means of detecting danger, we are deeply wired to respond to certain frequencies, such as a baby's cry. Communicating these dangers to others is a survival imperative. At the same time, laughter and sounds of ecstasy are just as innate to human vocalization. By observing the causes and effects of sounds in the environment, humans learn to interpret and interact with their world. By imitating animals, they are more effective hunters. By alerting others to attack, they improve chances of survival.

Over time, humans have learned to express complex thoughts and emotions through a variety of linguistic families. At the same time, we use sound for spiritual purposes — emulating beautiful bird songs, expressing awe at the mystery of creation, and voicing the depths of love and pain. The linguistic left brain wants to know “how and why?” but the emotional right brain doesn’t need an answer. Music touches us deep in our humanity, beyond the level of intellect and reason. When music and language combine, artists can express profound dimensions of human experience. This yearning to communicate our inner world — to know each other’s heart — is the epitome of human connection. Music and language allow us to touch and be touched more deeply.