Contributor Emma Camell recounts a recent trip to a drive-in theater and ponders the significance of such theaters during this moment when all moviegoers could use extra space to comfortably enjoy the show.

Like so many other people across the world, I also visited a drive-in cinema during the pandemic. Perhaps only the third such visit in my life. A local arts organization had recently opened the drive-in during Covid, and it was exciting to have an occasion to get out of the house and safely see other human faces. Looking around the “theater,” there wasn't much to speak of, just a gravel lot with a large screen, a food truck, a few porta-potties, and a projector booth, but despite the humble venue, the experience was rich.

My car was the first to arrive, about 30 minutes before showtime. Masked-up, we headed to the concessions stand, keeping a safe distance from the few other staff. Some text on the screen instructed the audience to tune into 88.3. A pre-picture soundtrack of spooky ambient music was played as we ate our popcorn. Suddenly, a voice came through my car stereo, “Alright movie-goers, we’ll begin the show in just a few minutes..” and the handful of headlights around us dimmed.

Front row seat at the Shotwell Drive-In. Photo by Author

The drive-in movie phenomenon was truly something to experience in the mid-1900s. Theaters were named things like “Starlite” and offered an evening free of worry, full of possibility. They fit perfectly into the American post-war lifestyle that soon influenced the whole world. Values like entrepreneurialism, suburban-automobile lifestyles, fast food production, and wholesome family entertainment were all combined at the drive-in complex. From the rocky early days to their late-century decline, various advancements in sound have shepherded the drive-in industry through these changes, to its lasting popularity today.

In the first years of drive-in cinemas, large loudspeakers were set up behind and next to the screen. An August 1933 issue of Electronics magazine described the technology behind the first drive-in in Camden, New Jersey: “R.C.A. Photophone high-fidelity speakers delivering 80 acoustic watts are used, enabling those seated in the rear rows, 500 ft. from the screen, to hear with the same clarity, as do auditors up in front.” However, other accounts described these huge speakers as “blasting” the sound too far into nearby neighborhoods, or the opposite, not even reaching cars at the back of the lot.

RCA, or Radio Corporation of America, installed small speakers in ground-level grates, with the intention of reaching the cars adjacent. An interesting experiment, but sonically it failed. Coming from the ground, the sound didn’t reach the audience's ears directly, and the ambient accumulative din of these small sound pits was as loud as the larger speakers. Curiously, RCA then tried a speaker that could be hung on a car’s bumper. The sound floated through the body of the vehicle, which produced a strange cavernous quality.

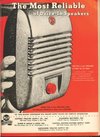

RCA drive-in speaker with volume knob

Keeping the movable speaker concept, RCA’s next version was built to hang inside a car window, and included a volume knob. Sturdy posts with these hanging speakers marked each parking spot. When the speakers were removed and hung on car windows, the sound actually entered the car interior. Finally, movie-goers could actually hear the soundtrack from inside the acoustic space of their vehicle, a natural amplifier. As large flat outdoor lots, drive-ins aren’t the best places for amplified sound systems, because the sound will dissipate quickly unless it’s at a very high volume. Inside a car comparatively, there are surfaces for the sound to bounce and reflect and grow off of, making it easier for anyone inside the car to hear.

Apparently the experience was more immersive, because many drivers forgot to remove the speaker before driving off, prompting animated PSAs about remembering to return them. Some editions of these speakers also included a Concessions switch, which would turn on a red light to signal an attendant, like a hand wave for a waiter in a restaurant. These were some of the special, interactive amenities that marked the “golden era” of drive-in theaters. The technology was so simple, but fulfilled really useful services.

Victor Villegas (Source)

Other companies began creating similar products to compete with RCA as the drive-in industry grew. This was the most popular and successful sound reproduction method, used from 1941 through the 70s. The system, whereby speakers were connected by cord to their posts, was also a way to help ensure that only paying moviegoers were able to hear the soundtrack, discouraging those who may have been parked freely nearby.

To connect all those speakers though, huge lengths of wires had to be run under the parking lot. In drive-ins that could hold up to three thousand cars, that was a serious project. Cables could be impacted or damaged by water, and the speakers were fully exposed to the elements. After a few decades of industry decline, broadcasting to car radios was more affordable for drive-ins and far simpler to implement.

The changeover to radio transmission was very common by the mid-70s. This was possible with microbroadcast transmitters, which can take over a radio wave and send the soundtrack to the immediate vicinity of the drive-in, but not much further. This way there’s no unwelcome intrusion on other broadcasts such as public radio stations. Microbroadcasting has also been used for pirate radio and other small-scale operations. The driver just has to tune in on their car’s stereo receiver. But any radio receiver in the area will work, and many cinemas will have extra radios on hand for any cars with broken equipment.

Photo by author

There is a technical sonic addition of microbroadcasting, which brings one away from the film and back into the driver’s seat. With the battery running to power the radio, drivers must intermittently turn their car off and on to keep the battery from dying, which interrupts the soundtrack, and creates a distraction of light and noise for other cars nearby. When I had to do this, though the mirage was briefly broken, it felt comforting to be in control of my own machine, to be in touch with technology.

Is there any room for improvement in the future of drive-in cinema sound? Considering advanced auto sound systems that exist today, a movie soundtrack from your car could be better than the theater. But with the screen further away, is the better audio quality really worth it without its visual counterpart? Audiophiles would likely have a better experience in an indoor theater.

Perhaps drive-in theaters best serve as a voyage to the past. Older drive-in cinema technology could follow in the path of cassettes and vinyl to renewed enthusiastic demand. In a pandemic-age where we’re afraid to touch everything, I would love a chance to toss that clunky RCA speaker into my car. Nostalgia for those days is very much alive, whether at revitalized drive-in theaters or from vintage drive-in technology collectors and historians. There’s something about watching a movie under the sky, inviting the environmental soundscape to intrude as it pleases. What are we watching? What are we hearing? In these times when screens have become personal appendages, the experience of a drive-in cinema can be even more powerful. So if you get a chance before it’s too cold, pull up to a drive-in, sit back, turn on your radio, and enjoy the show.