Ana Monroy Yglesias connects the rise & continuation of pirate radio, an "illegal" form of radio broadcasting, to state terrestrial stations lack of programming for the diverse communities they serve.

Imagine you’re a teenager in 1963 England—you love up-and-coming rockers The Rolling Stones and while you have one 12" of theirs, to hear their other tracks, and those of the like, you have to buy or borrow the records yourself since you can’t hear them on the radio. At the time, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), the U.K.’s state-owned broadcasting company, controlled the airwaves, and would only play a limited offering of pop songs on Saturdays. (The BBC still controls the British airwaves today, but they’ve adapted more to the times at least.)

Access to the music beyond the mainstream and classics was limited, as were the pathways to success for artists, until a young club owner and entrepreneur named Ronan O'Rahilly brought Radio Caroline to the U.K. O’Rahilly broadcasted to AM airwaves, from a ship outfitted with recording equipment and a massive radio transmitter, sailing the waters outside of British rule. This was the first wave of pirate radio—stations operating without official broadcasting permission—a new platform to share music, ideas, and information not touted by the mainstream.

Radio Caroline also offered a platform for Jamaican ska acts to be heard in the U.K. outside of sound system dance parties. By the late '60s, Jamaican artists like Desmond Dekker & The Aces, Harry J. All Stars, and The Pioneers all scored hits on the U.K. charts. In the early '70s, the BBC even launched its own Reggae Time show in response to the demand.

Radio Caroline became so popular, capturing the ears of about half of British listeners, that the government scrambled to maintain their control over the airwaves and passed the Marine Broadcasting Offences Act in 1967. While the law (which was repealed in 2007) did limit pirate radio, Radio Caroline remains on the air today, having stayed afloat on three different ships over the years and since 2018, held an AM broadcast license.

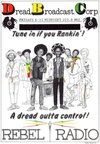

Another important era of U.K. pirate radio emerged in the '80s, with Leroy Anderson, known as Lepke, launching Dread Broadcasting Corporation (a.k.a. DBC, a play on BBC) from his backyard with a medium wave transmitter in 1981. Not only was it the first Black-owned pirate station, but it's credited as the first Black-owned radio station in Europe.

“I started the station because at the time there was a need for Black music to get more exposure: i.e., basically reggae music,” Lepke once said. “Then later on we moved on to broader Black music. Earlier in the '70s, I used to live in New York and I used to tune my radio in and hear pure Black stations, Spanish etcetera, So from them times I was thinking, maybe that can go on in England.”

Months into operation, the Department for Trade and Industry confiscated Lepke’s medium wave transmitter, so he sold tapes he'd already recorded for the show, eventually making enough money to buy an FM transmitter. The authorities tracked him for the three years he was on air—in this time, his studio was raided if broadcasters were “too left-wing,” and Lepke was even arrested at one point. As DBC gained popularity, it inspired other Black-run pirates to pop up. DBC DJs included Neneh Cherry, DJ Chucky, Gus Dada Africa, and Lepke’s sister, Ranking Miss P., who went on to become the first Black female host on BBC Radio 1.

Miss Ranking P (center)

"He reinvented the notion of pirate radio in the U.K. and established a template for Black British radio," wrote author and former DBC DJ Lloyd Bradley. "His proposal was devastatingly simple: run the station like a sound system, treat the shows with the same kind of intensity as a blues dance, and approach listeners as if they were a dancehall crowd who demand to be entertained. Effects, echoes, dubbing, toasting, jingles…bring it!"

Bradley also shares that Lepke wanted to get a license for the station to be able to operate legally, but was unable to. This underscores the "rebel with a cause" vision he and other pirate operators had—bureaucracy and the status quo wouldn't prevent him from providing a service, resource, and lifeline of joy to his community.

Even as DBC went off the air in 1984, the creative fire Lepke started in London raged on. He helped community members set up their own stations, and many of the DBC DJs continued their work on these platforms. At the beginning of the ‘90s, there were over 500 pirates operating in the U.K. His legacy of promoting and celebrating Black artists and genres created by those artists continued with stations like Rinse FM, Kool FM, RudeFM, Flava FM, and Pressure FM playing an important role in moving the emerging rave culture forward. These and other pirates played the freshest, hardest jungle, garage, drum and bass, house, and beyond.

Pirates also played an important part in the emergence of grime, a raw U.K.-specific rap form not intended for mainstream editing. Dizzee Rascal, Wiley and Skepta, who later found massive global success, all launched their careers from spitting bars on these stations.

"This whole scene was literally built off of pirates…None of the shit that I've done would've been able to go as far without pirate radio," U.K. grime rapper Jammer shared in a Rinse FM video. "You go on the radio station, you do your set. If it's not too bad, someone might've taped it, that tape gets passed around—someone's cousin that's in [London] from Birmingham goes back up to Birmingham [with the tape]. That was the internet, that was our network."

Rinse FM's reach has continued to broaden on a global scale thanks in part to being granted a community FM broadcast license in 2010, as well as internet broadcasting and their popular SoundCloud page (with 240,000 followers).

On SoundCloud, much like when operating as a pirate, radio broadcasting rules of censoring language don't apply. So while an FM license offers the freedom to broadcast without fear of fines, being shut down, and your equipment being confiscated, it limits the music you can play and what you can say. As former Rinse FM / current BBC Radio 1Xtra DJ and grime aficionado Sian Anderson pointed out, the legendary station's switch over to legal territory was significant.

"It made a huge difference: I ended up not playing tunes from my favorite artists… And with this being grime—as lyrically uncompromising as it gets—most of those MCs weren’t going to pay for the studio time to make clean versions of their tracks. Like me, MCs do not want to be censored. Grime has always been about freely venting your frustrations…That’s why pirate radio is such an essential platform for emerging voices—but the British authorities have done their best to stamp it out. Running a radio station without a license to broadcast was made a criminal offense in 2006."

Even as governments continue to crack down on pirate radio, it will continue to exist, both on the airwaves and online. Kool, now KoolLondon, streams 24/7 online, while still broadcasting from its pirate FM frequency. In 2018, The New York Times reported a sharp decline in U.K. pirate radio, in part because of internet streaming:

"Kool’s problems are part of a broader trend: Ofcom, the British communications regulator, estimated there are now just 50 pirate stations in London, down from about 100 a decade ago, and hundreds in the '90s, when stations were constantly starting up and shutting down. Ofcom considers this good news, because illegal broadcasters could interfere with radio frequencies used by emergency services and air traffic control, a spokesman said. But pirate radio stations also offered public services, of a different sort: They gave immigrant communities programming in their native languages, ran charity drives and created the first radio specifically for Black Britons."

While pirate radio in the U.S. has had a somewhat more lowkey existence over the decades than its counterparts across the pond, it continues to thrive despite attempts by the FCC to squash it completely.

In 2021, journalist David Goren estimated around 100 pirate stations were in operation in New York. He has tracked over 60 from his home of Brooklyn, some of them now defunct or online-only, on the Brooklyn Pirate Radio Map. Like London, Brooklyn (particularly Crown Heights), is home to a large population of Jamaicans and other ethnic groups from the Caribbean diaspora, who’ve brought with them the food, music, and other cultural gems from their homeland. Some have turned to radio as a tool to share sounds from home, as well as news and information relevant to their local community, in the language or dialect that directly speaks to them. There’s Krystal FM, which delivers live song and conversation in Haitian Kreyól, GospelReggaeAM, as well as stations that link with an international one, like the now-defunct Word 107.1 relay from Trinidad.

“[Pirates] offer a kind of programming that their audiences depend on. Spiritual sustenance, news, immigration information, music created at home or in the new home, here,” Goren told the New Yorker in 2018. He adds that most of the stations are "Caribbean, Latino, and Orthodox Jewish," and shares a clip from Triple 9 HD, where a lawyer recommends a hotline for immigrants facing legal issues.

That same year, Donald Trump-appointed FCC Chairman Ajit Pai introduced the Preventing Illegal Radio Abuse Through Enforcement Act (PIRATE Act) to Congress, which went into effect April 2021, increasing pirate radio fines from a maximum of $140,000 to two million dollars! According to ffc.gov, the government agency has shut down hundreds of pirate stations across the country between December 2012 and July 2020, including 141 in New York, 176 in Florida, 89 in Massachusetts, and 83 in New Jersey. Licenses are expensive and may not even be available to most; Low Power FM Radio licenses may be granted at no cost to schools, non-profits, religious groups and Native American tribes, but not to individuals or already existing broadcasters.

Joan Martinez, a New Yorker born to Haitian parents, grew up listening to pirate Haitian stations and cut her teeth at one while finishing her graduate studies in broadcasting. In 2019, she spoke to The Verge on the power of pirate radio and the harm inflicted by the PIRATE Act:

“Here’s the thing: people use the radio as that warming voice, that sort of hug. It’s nice to know that the person that’s hugging you is somebody that speaks your language. It’s somebody that knows your struggle. It’s somebody that’s listening to you.

They say that there are no licenses available in New York, supposedly, and the license is like $1 million. Do you really think that a bunch of blue collar guys, they can pull together enough money to get a license, and are you going to help them do that?”

DBC DJ Camilla, who was also a full-time social worker, spoke on the station’s mission to help, spurred by her own urging: “I would go to station meetings and tell them we needed to be doing more for the community, like talking about sickle cell anemia and the need for more people in the community to donate blood.”

As the legacy of pirate radio continues online, it's inspired a new batch of online stations to promote fresh and diverse sounds and artists, like NTS Radio in London (with over 50 broadcast cities!), Kiosk Radio in Brussels, dublab in Los Angeles and The Lot Radio in Brooklyn. Skate brand Vans has even followed suit with Channel 66, featuring music and conversations broadcast live from its studios in L.A., Chicago, New York, and Mexico City.

(EIC Spurge recently on NTS^)

Most FM radio music stations offer a narrow format of hits or popular genres, with commercials filling the rest of the space. College and public radio stations offer DJs a bit more freedom and listeners a bit more variety, but, as evident through its U.K. beginnings and various outgrowths like in Brooklyn, pirate radio offers much needed programming for communities left out the rest of the dial.